Nostromo by Joseph Conrad.

Welcome to the Republic of Costaguana, in some fictional South American location but most likely somewhere on the Pacific coast occupied by real-life Colombia. If you don't like the weather, well, there'll be some different weather sweeping down from the coastal mountains in a few minutes; if you don't like the government, well, pretty much the same rules apply. We are in the coastal town of Sulaco, largely cut off from the rest of Costaguana by a high mountain range, and mainly accessible by sea.

People in Sulaco are generally just regular people trying to get through the day and make a living; those that aspire to greater things have a problem to deal with: you probably need help from the government, or at least some sort of understanding that they'll leave you alone and let you get on with your business. The trouble is, if you yoke yourself too explicitly to one particular governing regime, you'll be in a slightly awkward position when a different governing regime comes along, with the usual ruthless purges of those felt to be too inflexibly loyal to its predecessor.

Case in point: Charles Gould, English by blood but born and raised in Costaguana, owner of the San Tomé silver mine and very keen to see it productive and turning a profit. Trouble is, you can't run some massive industrial operation involving excavating most of the inside of a mountain without it attracting attention. Nice silver mine you've got here, shame if it was to CATCH FIRE, and so on. Gould has come to an arrangement with the current regime, but then the inevitable glorious revolution happens and all bets are off. In a panic Gould decides to take all the stash of silver ingots that he's been keeping in a Sulaco dockyard warehouse and get some trusted men to take them off in a ship and hide them somewhere more discreet. These trusted men turn out to be Giovanni Battista Fidanza, expatriate Italian, Capataz de Cargadores (i.e. head longshoreman), local legend, widely known to most as Nostromo, and, less obviously, Martin Decoud, Frenchman and editor of the local newspaper.

Nostromo and Decoud take a shitload, sorry, shipload of silver ingots away from Sulaco but on their way out towards the open sea have a close encounter with an incoming ship carrying some advance troops from the new regime and have to make an emergency landing on one of the Isabels, the island group that guards the entrance to Sulaco harbour. Nostromo swims all the way back to Sulaco, leaving Decoud to guard the silver and generally contemplate the futility of existence in solitude.

The new regime's reign of terror is mercifully brief and is brought to an end by another glorious revolution sweeping over the mountains and liberating Sulaco, just as certain high-profile residents (Charles Gould, for one) were about to be strung up for being insufficiently deferential and (in Gould's case) not handing over the deeds to the mine. The story has got about that the boat carrying the silver sank after the collision, which means no-one's expending much energy looking for it. Now obviously Nostromo could tell the authorities where it is, but he's a bit put out at the lack of recognition for his heroics and decides not to. You can't just wander into town with a coat full of silver ingots with Property of San Tomé stamped on them and expect to be able to exchange them for various consumer goods without arousing suspicion, though, so Nostromo hatches a plan of gradually spiriting them away by sea to distant ports and exchanging them there.

This all works OK for a while, but it's slow. So you can imagine Nostromo's dismay when plans are hatched to built a ruddy great lighthouse on top of the Great Isabel where most of the silver still resides. Nostromo is nothing if not resourceful, though, and contrives to have his old friend Giorgio Viola installed as lighthouse-keeper, which gives him a pretext to sail over and visit, especially as it's always been assumed that Nostromo will marry Viola's elder daughter, Linda.

So, everything's fine, then? Well, no, as having hung out with the Viola family a bit Nostromo decides that actually Linda is a bit feisty for his liking and that actually he'd prefer her younger sister Giselle, more delicate and pale-skinned and apparently timid and demure, though with just a suspicion of ABSOLUTE FILTH on the quiet. An unfortunate incident ensues where Nostromo sneaks along the beach to Giselle's window for a night-time assignation and is shot by her father, lingering long enough to be transported back to Sulaco for some mournful farewells before expiring.

This is the first Joseph Conrad book I've ever read (although he did get a brief tangential mention here), and I picked up my Penguin Twentieth-Century Classics edition for a couple of quid in a charity shop for £2 several years ago. If I'd read Giles Foden's lengthy Guardian Conrad profile wherein he describes the forbiddingness of Conrad's prose and of Nostromo in particular ("probably the most difficult to read of all Conrad's novels") I might have had second thoughts about the whole affair, and overall I'd say that would have been a shame, for all that I do see what he means. There are sections describing the political backdrop to the events in Sulaco that are pretty daunting walls of text; equally, though, some of the sections describing Nostromo and Decoud's seafaring adventures are genuinely thrilling. You'd have to say the overall tone is generally fairly pessimistic, though, all the characters being eventually corrupted either by political ambition or simple greed, even, eventually, Nostromo himself. The few characters who are sympathetically portrayed get a pretty raw deal as well, most obviously the fragrant and lovely Emily Gould, wife of Charles, of generally saintly disposition and well-disposed towards the poor and underprivileged. It's made clear, though, or as clear as it can be in a novel published in 1904, that she is keen to have children and keen for A Portion in a more general sense but is Not Getting Any because old Charles is off tending to his mine workings instead of, as it were, detonating something in, if you will, her tunnel.

You will recall a couple of lists of reading Projects that I shared on Twitter over the course of the last couple of years, and that Nostromo appeared on both lists, along with a few others.

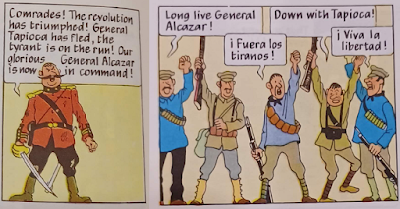

The other thing I was put in mind of on reading this, with reference to the regular changes of governing regime in particular, was the Tintin book The Broken Ear, which features a running joke about the regular changes of regime in the republic of San Theodoros:revised list follows: Jane Eyre, Don Quixote, Nostromo, Foucault's Pendulum, The Lay Of The Land, The Mayor Of Casterbridge, Ulysses, Blonde, The Book Of Disquiet, Swann's Way, Gravity's Rainbow, Cancer Ward, Tristram Shandy, The Goldfinch, Anna Karenina, Germinal. https://t.co/1YaHStc5gY

— Dave Thomas (@electrichalibut) November 16, 2021

No comments:

Post a Comment